In today’s age, recycling presents a paradox. It provides hope for the sustainable reuse of packaging but is concurrently impeded by confusing infrastructure, guidelines and supply chain issues.

Fittingly, a panel held at London Packaging Week 2023 expressed the perplexities surrounding recycling in its confusing title: ‘The Big Question: What is the Goal?’ and subtitle: ‘To have a clear vision is to know how to get there’.

Intentionally or otherwise, these titles encapsulate the mire surrounding modern recycling efforts, which represent questions, goals, and visions with no clear answers.

Attempting to provide answers were the panellists founder and chairman of Plastic Bank David Katz, OPRL managing director Margaret Bates, WRAP strategic technical manager of plastics Jayne Paramore and the Foodservice Packaging Association (FPA) executive director Martin Kersh.

The panellists shared their frustrations on a lack of government support for consistent national recycling but struggled to agree on accountability for businesses and consumers.

Are consumers to blame for poor recycling?

Martin Kersh kicked off the discussion by asking the audience whether they believe citizens want to change their behaviour to improve recycling.

Half of the audience agreed that citizens are motivated to recycle properly and efficiently. But Kersh disagreed, using the London Packaging Week event as his example:

“The bins here say that recyclables need to be cleaned. But for an hour I’ve watched people in this very building putting in food and all sorts of stuff into the bins. And when you point this out, they say ‘I saw but I just did it anyway’.

“Now we’re informed, knowledgeable people who still behave like this. So, do we really believe that citizens will take the steps to put things in the right bin? I’m personally very cynical about citizen participation.”

David Katz took a more existential view, placing the future survival of humanity on the reuse and repurposing of all materials.

Katz admitted that there is a journey to get there but rejected Kertz’s cynicism.

“I would argue that the population does want something to do with circularity. I’m inspired in the knowing that the perfect is the enemy of the good enough. I understand the ambitions to have pure circularity, but as humanity we need to start.”

Consumer education on materials

ORPL managing director Margaret Bates addressed the negative perception of plastic materials among the general public.

“Everyone in this room thinks plastic is great. Everyone outside this room thinks plastic packaging is terrible. We need to be practical about how we communicate these issues and I don’t think the government help.”

Bates asked the panel if the goal should be to have no packaging at all.

Jane Paramore stated that there will always be a need for packaging, but “We need to make sure we have the most efficient and effective material that can be put back into the circular system as many times as possible. We want consumers to feel like they are getting something better.”

She also spoke against engineered materials that are designed and marketed to replace plastics but actually aren’t recyclable.

Paramore’s focus was on “creating a system that consumers can participate in and find the convenience that they get from the current system.”

Katz agreed that there will never be a world without packaging: “It should never be a world without plastics either. But it should be a world without waste and there needs to be incentives.”

There was a general agreement that the younger generation of consumers are practising sustainability and want to buy unpackaged products but have few if no options to do so.

Bates stated that part of the problem is consumers expecting their “unsustainable lifestyles to be supported in a sustainable way.”

The recycling class divide

An arguably overlooked aspect of recycling discourse is that its accessibility differs between social classes.

Katz disagreed that consumers should have to pay more for sustainable and recyclable materials.

Bates pointed to recycling efforts by discount retailers, which she says offer environmental solutions to consumers who aren’t middle class.

“We keep coming up with solutions that only apply to the upper and middle classes. But if you’re struggling, in socially disadvantaged circumstances, being told how to recycle when you can’t afford it and don’t have the time doesn’t help.”

An audience member asked the panellists for examples of companies and brands helping consumers to make better choices. The panellists highlighted Unilever, SC Johnson and Lidl.

It remains unclear what difference consumer behaviour really makes when wider infrastructural and capitalistic systems remain entrenched. For example, a recent study found that the UK is estimated to mismanage 250,000t of plastic waste in 2023 alone.

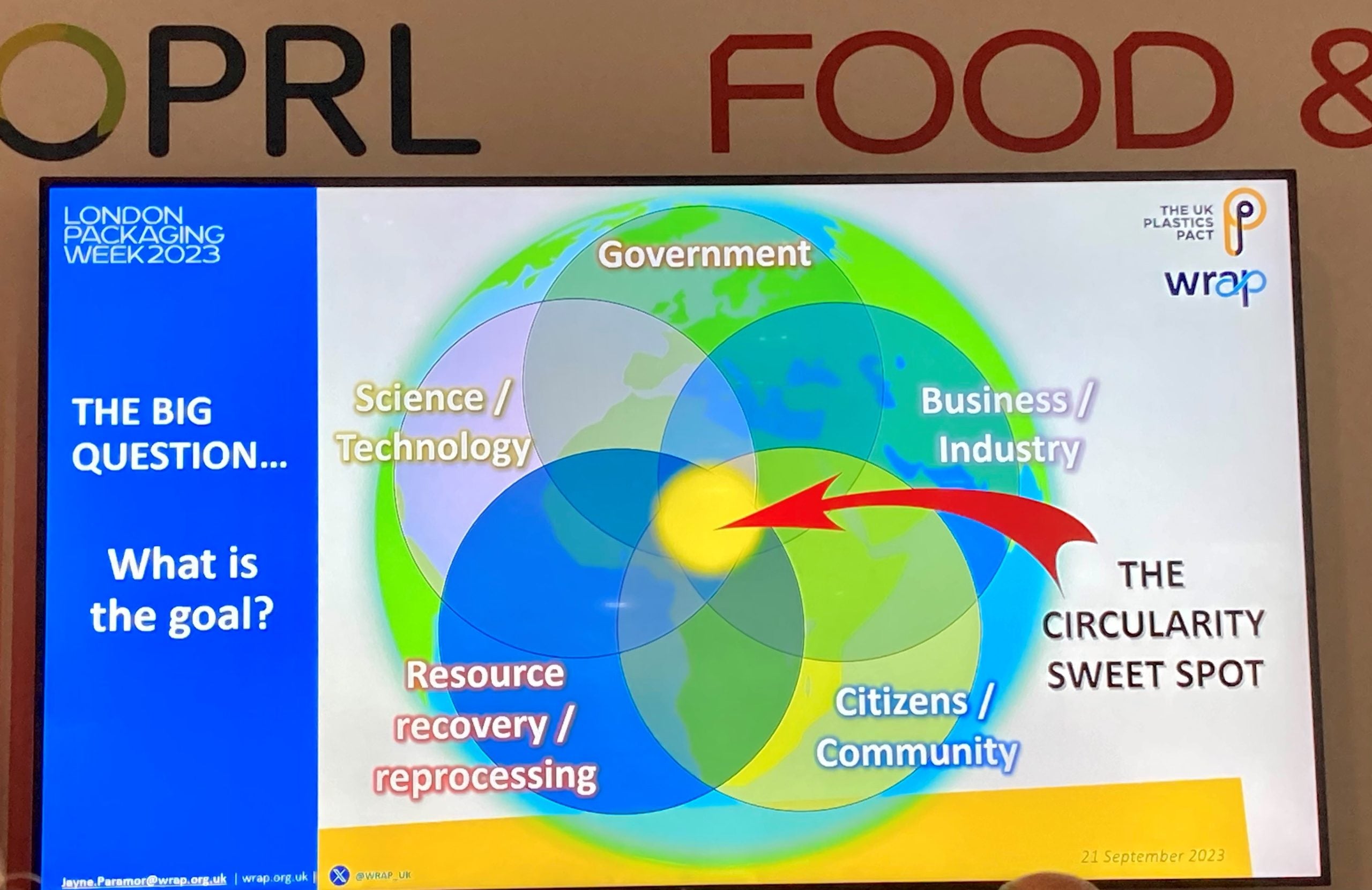

Paramore proffered that the “circularity sweet spot” exists in cooperation between citizens, businesses, government, science and resource recovery.

But if panellists discussing the topic of recycling cannot agree on key points, it remains unclear whether any such cooperation can be achieved.