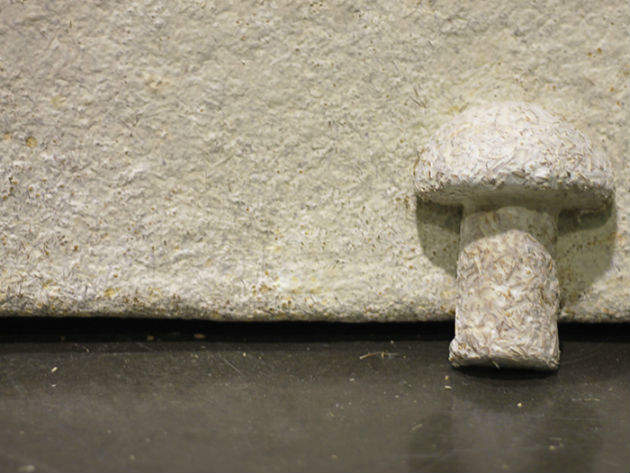

Image: Does mushroom packaging hold the key to reducing the use of enviornmentally toxic polymers? Photo: courtesy of Ecovative

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

The negative environmental impact of polystyrene and styrofoam, courtesy of the toxic nature of styrene is long known and large. Back in 1986, a report by the US Environmental Protection Agency found that the manufacturing of the material was the fifth largest creator of hazardous waste. Composed of a combination of the carcinogens styrene and benzene, and created through the use of environmentally damaging hydrofluorocarbons, its mere materialisation is a point of climate conscious regret, but far from its overall flaw.

Once produced, its use is even more of an issue. Light in weight and expensive to prepare for recycling, it is largely left as rubbish. As a consequence, it populates much of the world's landfill sites, fills its bins, litters its streets and pollutes its waters more than any other material. But more objectionable than any of its other properties is its staying power. Cast aside a polystyrene coffee cup into a compost heap and it won't fully decompose for at least half a millennia.

It is, on all accounts, environmentally absurd. But when it comes to packaging, it's really rather handy. Part of the, until recently, bottomless pit of petroleum processed plastics, it is incredibly easy to shape and mould, but sturdy to hold its shape, and crucially, affordable. Based on these factors alone it's no wonder it’s the go-to force material in containing the take-away coffees, protecting the computers, and amusing children more through packaging than the present packaged the world over.

But times have changed since German apothecary Edouard Simon accidentally invented it while distilling sweetgum tree resin in 1839, and continue to change apace since Dow Chemical put its commercial weight behind the global expansion of its trademarked design of the dominant Styrofoam.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataCountries are collaborating and leaders from politics and business conversing in Davos on how to tackle climate change and bring about a more sustainable world. And a major win within that, would undoubtedly be to move away from a polluting packaging material and towards a naturally harmonious one.

Making natures take its course

It may well be mushrooms, which hold the magic solution. Brought together at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute under the tutelage of renowned academic Burt Swersey, Eben Bayer and Gavin McIntyre fully embraced the private university's mantra of applying “science to the common purposes of life.” Driven by a belief that the world needed ’better materials’ that fitted into ‘nature's recycling system’, the two students sought to identify a material that complied with three key principles.

First of all, it had to break the monopoly of petroleum processed materials, secondly, the manufacturing process had to be far less energy intensive, and third and most important, it had to fit into what Bayer refers to as 'nature's recycling system', a material that could be absorbed into the earth in a natural manner, as opposed to polystyrene's 500 year strong staying power.

Explaining his view in a TED Talk, Bayer said: “We should be creating materials that fit into what I call nature's recycling system. This recycling system has been in place for the last billion years. I fit into it, you fit into it, and a hundred years’ tops, my body can return to the Earth with no pre-processing. Yet that packaging I got in the mail yesterday is going to last for thousands of years. This is crazy.”

Guided by that motivation and the aforementioned principles, Bayer and McIntyre eventually found that the natural properties and workings of Mycelium provided all that was needed to develop the material they were seeking. “By using a part of the mushroom you've probably never seen, analogous to its root structure, called mycelium, we can actually grow materials with many of the same properties of conventional synthetics.”

Having developed an initial design at RNI, which they patented, they then established Ecovative Design, thanks to receiving various grants and research funding, to further explore its potential and set about commercialising the process.

That process, which operates the same way today, complies with each of the founding principles. Far removed from petroleum, the feedstock can be drawn from a range of natural waste such as seed husks or woody biomass, which the mycelium can naturally transform into a polymer with all the same properties of conventional synthetics. Due to the wide range of organic waste feeds from which it can work, the process can work with locally available waste, lowering both the environmental impact of transport and the cost.

Shaping a brighter future

Once sourced, the feedstock is put into a pre-made mould to define its shape, from this the mycelium grows and binds the material over a period of around five days to produce the final material, whether that be a table top, a building block, or indeed a packaging material with all of the material benefits of polystyrene but drive by an organic and natural manufacturing process rather than an energy intensive one.

But beyond the savings in the manufacturing of it, the disposal is vastly more favourable. The end product, once used, is 100% compostable, meaning its disposal adds nutrients to the ground rather than attacks them.

The material's comparable quality to polystyrene, combined with its strong alignment with the ever growing pressure for stronger corporate sustainability, has helped Ecovative quickly gain a high profile at top tables. In addition to being invited to give a TED Talk, the company was voted 'Coolest Start-Up' at the World Economic Forum at Davos in 2011 and has since been invited back to the conference which mixes world leaders with top executives at the world's most powerful companies.

Taking polystyrene to task

From addressing leading brands at exclusive events, the company then sealed its highest profile deal when computer giant Dell announced that it would work with Ecovative to develop mushroom packaging to protect its computer servers while in transit. In addition, the company agreed a licensing deal with packaging specialists Sealed Air, which has reached agreements with a number of firms to use the process, including laboratory equipment manufacturer Stanhope Sets, which ships its products around the world, and solar powered consumer product manufacturer Spor, which opted for the material to fit with its environmental goals.

It was earlier this year though, that the company received its biggest endorsement in the packaging world, when Swedish retailer IKEA appeared to indicate that it was looking into replacing polystyrene with mycelium packaging. Speaking at a conference in London, Joanna Yarrow, IKEA’s head of sustainability in the UK, said: "We are looking for innovative alternatives to materials, such as replacing our polystyrene packaging with mycelium – fungi packaging."

With the company confirming that it is investigating the material, it appears that Ecovative's intention to displace what it calls an 'egregious offender' to the environment with one in harmony with nature, is moving closer to reality. However, such progress will also bring its biggest challenges. That polystyrene is the primary source of urban litter stands as a point of environmental concern, but it is also a strong indicator of just how embedded it is with the modern world. It has been the go to material for everything from CD cases to coffee cups for many decades and overtaking anything of such scale will not simply be a case of offering an environmental alternative.

The process has been proven to work and produce a material that competes on material grounds. But to become a true and viable alternative, it must now prove that it can also compete on scale and price. A deal with IKEA, or a similarly high profile global player with a strong track record on sustainability, would give it that opportunity, and if it can succeed, may well put it in a position to launch a strong attack on polystyrene and prove a vital tool in the fight against climate change.